Al Clark: “Nobody grows up wanting to be an umpire”

By Stuart M. Katz, correspondent

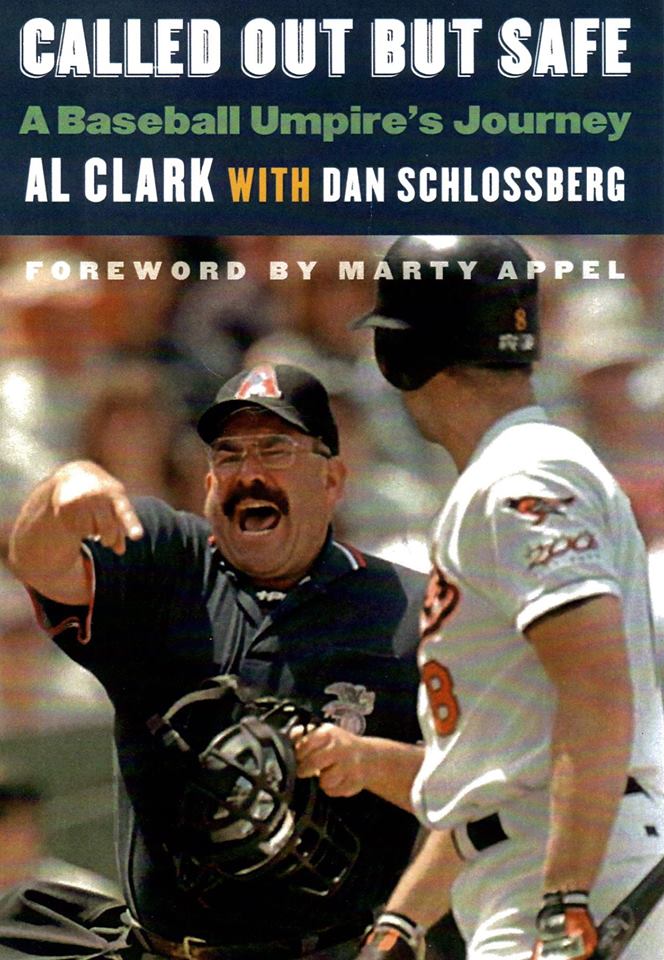

When he was growing up in Trenton, N.J., Al Clark’s family thought he might become a rabbi. They couldn’t have imagined that he instead would spend more than 25 years on Major League Baseball fields as the American League’s first Jewish umpire. From 1976 to 2001, Clark had a bird’s eye view of some of baseball’s most iconic moments. His new autobiography – Called Out But Safe: a Baseball Umpire’s Journey — chronicles his amazing career. (Click here for an excerpt.)

In a recent interview, Clark discussed his Jewish upbringing, his career, and the lessons he has learned from making some bad choices along the way, including one that landed him in federal prison. Here is an edited version of the interview.

JBN: Did you grow up in an observant home?

Clark: I grew up in Trenton. My father was from New York and my mother was from Springfield, Mass. My grandparents all came from Europe. We were a practicing Jewish family. I had my Bar Mitzvah at Ahavath Israel in Trenton, where I loved attending Hebrew School and Sunday School. After my Bar Mitzvah, I learned to blow the Shofar, and our Rabbi invited me to blow it on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, in front of the entire congregation. Talk about pressure!

JBN: How did you decide to become an umpire?

Nobody grows up wanting to be an umpire. I played baseball in high school and then attended college at Eastern Kentucky University. After college, I taught for a period of time but didn’t enjoy it. I worked as a journalist, and enjoyed that, but I wanted to eat steaks instead of hamburgers and became interested in being an umpire.

JBN: What training did you get to learn how to be an umpire?

Clark: I had to go to umpire school. It was a five-week course in St. Petersburg, Florida. When I completed the course, I was fortunate to get a job in the minor leagues, where I enjoyed a few different assignments before the American League (of Major League Baseball) took an option on my contract. I was fast-tracked to the Majors, and got there with just under 4 years of minor-league experience.

JBN: What else in your life helped prepare you for the spotlight of umpiring?

Clark: My father was a writer. Starting in about 9th grade, he required me to read a book every month. For every book, I had to write a book report, which he then had me recite out loud while standing at attention. This training made me proficient as a writer and ensured that I was never afraid to speak in public, or to walk out onto a field with 50,000 people in the crowd.

JBN: How would you describe the life of a Major League umpire?

Clark: Umpires are unionized, so under our contract, we would work 145 games per year, not including spring training or the post-season. We worked with the same crew all season. I worked with one crew for about 8 years, and another for about 7 years. The starting salary when I got to the big leagues was $15,500, although it is much higher now. By the time I finished in 2001, I was earning around $384,000. Because of all of the travel involved, I would leave home every March and not return until October, crisscrossing the country many times each season.

JBN: What was the most iconic moment that you witnessed?

Clark: That is a really great question. I would have to say that Cal Ripken breaking Lou Gehrig’s record for consecutive games. It was absolute magic to be in Baltimore that week. I was behind the plate on the day he tied the record and at third base when he broke it. That was one game where I really felt like a spectator.

JBN: What were some other highlights for you?

Clark: I was chosen for the crew of the one game playoff in 1978 between the Yankees and Red Sox. That was a great honor, since I was selected in my third year in the league. I also worked the 1989 “Earth Quake” World Series, which was very memorable. I was at Randy Johnson’s first no-hitter, and Nolan Ryan’s 300th win. I lived the dream. I loved my work.

JBN: Did you ever experience anti-Semitism on the job?

Clark: Never at the big league level. The only incidents were in the minors. The most memorable one involved a former Cy Young award winner who was on his way down and out. After a game in Indianapolis, he and a teammate waited for me and verbally attacked me. This incident shook me a lot, because I had never been subjected to something like that. Fortunately, there was a swift and stern reaction from the league president, with immediate suspensions for the players involved.

JBN: What do you think about the instant replay?

Clark: I love it. Its time has come. With HD and the amount of cameras around the park, it will raise the level of quality of umpiring to a level it has never been at before.

JBN: Your career ended because you got fired; what happened?

Clark: I was catching a flight after a game that went into extra innings and had to change my travel arrangements. The only seat available was a first class ticket. I upgraded, which was permissible, but didn’t call the league office to explain what I had done, which was required. I could have been suspended or fined, but they decided to fire me. I think that because the umpires’ union was so strong, they figured if they could make an example of a 26-year-veteran, then everyone else would be in line.

JBN: Did you challenge the termination?

Clark: I could have probably filed a grievance for discrimination, but I was 18 months away from retirement and I opted not to go that route. I loved Major League Baseball for 26 years, and fighting the decision would have tarnished the experience.

JBN: Why did you decide the write this book now?

Clark: I realized that I was eyewitness to many iconic things that happened during that 25 years in baseball. An ump’s eye view is a different perspective.

JBN: Are you worried that people will focus on your firing and your later incarceration for mail fraud (resulting from a memorabilia scheme), rather than your time as an umpire?

Clark: My termination and incarceration are not going to define Al Clark. They are things that happened. People who don’t know me may form opinions. I tried to make my time in a prison camp productive. I learned a lot about patience. Time in prison doesn’t go fast, nor does it go slow. I gave a 6-week course for other inmates, teaching the guys to be sports officials. I started a website when I got out to help people who were going to prison, who never expected to find themselves in that situation. To this day, my federal prison number is on the mirror in my bathroom. It serves as a reminder that every day, we have decisions to make and better make the right ones.

# # #